In 2019, Muaz Razaq departed from Pakistan for the first time to pursue a master’s degree in computer science in South Korea. Little did he know that this journey would thrust him into the center of a contentious battle that would test the country’s commitment to religious tolerance.

“I chose Kyungpook National University in South Korea due to its reputation as a leader in software engineering and the presence of a nearby mosque, which my seniors had spoken highly of,” shared the now 27-year-old doctoral student in an interview with Al Jazeera. “Although locals sometimes showed curiosity about my traditional attire and beard, reminiscent of Korea’s past aristocrats, I never experienced animosity or direct discrimination.”

However, everything changed when the university’s approximately 150 Muslim students decided to renovate the mosque they had established near the west gate of the campus in 2014.

This development project quickly became a focal point for virulent Islamophobia, transforming the construction site into a battleground.

Situated in the Buk district of Daegu, South Korea’s third-largest city and a conservative stronghold, the mosque—officially known as Dar-ul-Emaan Kyungpook and Islamic Centre—serves as a center for the Muslim community, located approximately 240 kilometers (149 miles) from the capital city, Seoul.

Daegu is home to several mosques, mainly located in the suburbs, catering to the practicing Muslim migrant labor populations.

The students embarked on raising funds to demolish their previous cramped and poorly heated building adjacent to the university, with the intention of constructing a new two-story facility. As part of the process, they acquired the neighboring house, which currently functions as a temporary prayer hall.

However, shortly after the new structure’s beams were erected in early 2021, the Buk district office suddenly issued an administrative order to halt construction, citing complaints from local residents.

Reportedly, the concerns raised related to the smell from the students’ cooking within the mosque, noise levels, and potential traffic disruptions—issues that Razaq claims had not been previously mentioned or regarded as problems.

In no time, pamphlets started circulating throughout the surrounding streets, spreading claims that the area would deteriorate into a “slum” and property values would plummet. Students found themselves unjustly labeled as “terrorists,” and offensive banners were plastered across the streets. Rallies took place, accompanied by blaring music right outside the temporary prayer room.

In the face of these mounting hostilities, the country’s human rights watchdog recommended that construction should resume. In 2022, the Supreme Court ruled that the administrative order to halt construction was unlawful. Despite these decisions, the hatred and animosity persisted.

Provocative pork barbecue parties were held directly in front of the construction site, and pig heads were callously left as menacing symbols.

Claiming it was a matter of self-preservation, Kim Jeong-ae, the leader of one of the resident opposition groups against the mosque, expressed her perspective to Al Jazeera during a press conference held outside the Buk district office. The opposition groups accused the officials of siding with the students.

Concerns over potential break-ins led rows of civil servants to barricade the entrance of the district office, with police standing by as a precautionary measure.

Kim Jeong-ae further emphasized that the Muslim students were “welcome to choose any other location” apart from the narrow alley where the mosque was situated. She believed this was a necessary step to safeguard their lives.

Yi Sohoon, a sociology professor at Kyungpook National University and president of the Taskforce for the Peaceful Construction of the Islamic Mosque, argues that concerns about smells and noise are mere pretexts to obstruct the project. In an interview with Al Jazeera, she asserts that it is impossible to separate genuine concerns from those fueled by xenophobia and Islamophobia. She believes that all legitimate worries can be adequately addressed.

The students involved in the mosque construction have already made commitments to address the concerns by installing an extractor chimney and implementing soundproof walls and windows. Contrary to rumors, there were never any plans for an external loudspeaker for the Islamic call to prayer.

In Daegu earlier this month, a chilling sight was discovered at the construction site—a fridge containing three rotting pig heads and trotters. Additionally, a plastic pig’s head was positioned next to a banner proclaiming, “People first! Against the construction of the mosque!” These actions were recently condemned by the human rights commission as typical expressions of hate, targeting a minority group based on race and religion. The commission stated that these acts aimed to demean Islamic culture and incite hostility towards Muslims.

Representing the university’s Muslim students, Razaq blames specific religious groups for the attacks on his community, asserting that they are coercing locals to turn against them. According to him, South Korean media has been reluctant to address this aspect of the dispute. He believes that omitting this information leads the public to perceive the situation as a simple dispute between neighbors and Muslim students, while in reality, these religious groups have been actively disseminating Islamophobic information and mobilizing resources to disrupt the peaceful resolution of the issue.

Enter the Christian lobby group: Protestants account for approximately 20 percent of South Korea’s population, equivalent to 10 million people. These conservative evangelical groups, often associated with far-right politics, hold significant influence in politics and society.

In contrast, the Muslim population in South Korea is estimated to be fewer than 200,000, consisting mostly of foreign nationals.

Farrah Sheikh, an assistant professor specializing in Islam in South Korea at Keimyung University, attributes Islamophobia to various factors, including the circulation of fake news and distorted information from foreign sources. She also highlights the negative perceptions shaped by well-organized and well-funded extreme Christian right groups, who fear an alleged “Islamic invasion” through the introduction of Muslim facilities like halal food or prayer spaces, as well as the acceptance of Muslim refugees.

Recent studies have shown that the Christian right in South Korea has initiated a “culture war” with a particular emphasis on opposing Islam and the LGBTQ+ community. This group is a significant obstacle preventing the passage of an anti-discrimination law in South Korea for over a decade.

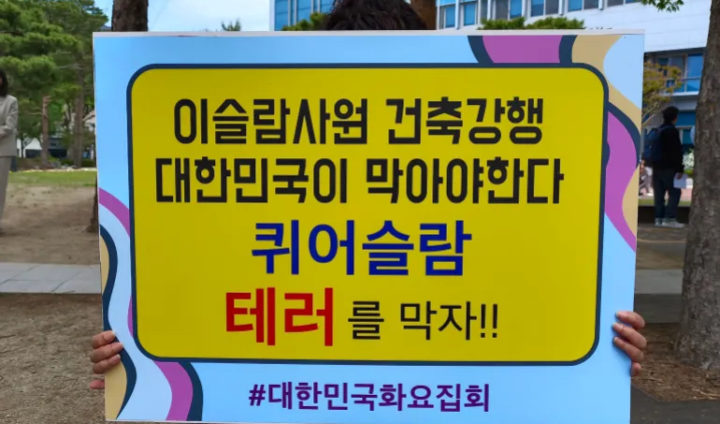

A poster held by an anti-mosque protester outside the Buk district office further demonstrates this conflation of issues, calling for the blocking of “queerslam terrorism,” combining the words “queer” and “Islam.” The suffix “-slam” is derived from Korean internet slang, signifying irrational behavior or blind following.